Julian Assange arrested after

Ecuador tears up asylum deal

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been evicted from the Ecuadorian Embassy in London where he has spent the last six years. Ecuador's president has announced that the country has withdrawn asylum from Assange

The eviction follows reports that the Australian founder of the WikiLeaks whistleblowing portal would be handed over to British authorities. Ecuador denied the reports and said it had no intention of stripping him of his protected status, but apparently another decision was made by Quito.

Assange's relationship with Ecuadorian officials appeared increasingly strained since the current president came to power in the Latin American country in 2017. His internet connection was cut off in March of last year, with officials saying the move was to stop Assange from "interfering in the affairs of other sovereign states."

USA is always interfering in the affairs of other sovereign states

The whistleblower garnered massive international attention in 2010 when WikiLeaks released classified US military footage, entitled 'Collateral Murder', of a US Apache helicopter gunship opening fire on a number of people, killing 12 including two Reuters staff, and injuring two children.

The footage, as well as US war logs from Iraq and Afghanistan and more than 200,000 diplomatic cables, were leaked to the site by US Army soldier Chelsea Manning. She was tried by a US tribunal and sentenced to 35 years in jail for disclosing the materials.

Manning was pardoned by outgoing President Barack Obama in 2017 after spending seven years in US custody. She is currently being held again in a US jail for refusing to testify before a secret grand jury in a case apparently related to WikiLeaks.

USA should NOT have secret grand juries

Assange's seven-year stay at the Ecuadorian Embassy was motivated by his concern that he may face similarly harsh and arguably unfair prosecution by the US for his role in publishing troves of classified US documents over the years.

His legal troubles stem from an accusation by two women in Sweden, with both claiming they had a sexual encounter with Assange that was not fully consensual. The whistleblower said the allegations were false. Nevertheless, they yielded to the Swedish authorities who sought his extradition from the UK on "suspicion of rape, three cases of sexual abuse and unlawful compulsion."

In December 2010, he was arrested in the UK under a European Arrest Warrant and spent time in Wandsworth Prison before being released on bail and put under house arrest.

During that time, Assange hosted a show on RT known as 'World Tomorrow or The Julian Assange Show', in which he interviewed several world influencers in controversial and thought-provoking episodes.

His attempt to fight extradition ultimately failed. In 2012, he skipped bail and fled to the Ecuadorian Embassy, which extended him protection from arrest by the British authorities. Quito gave him political asylum and later Ecuadorian citizenship.

Assange spent the following years stranded at the diplomatic compound, only making sporadic appearances at the embassy window and in interviews conducted inside. His health has reportedly deteriorated over the years, while treatment options are limited due to his inability to leave the Knightsbridge building.

In 2016, a UN expert panel ruled that what was happening to Assange amounted to arbitrary detention by the British authorities. London nevertheless refused to revoke his arrest warrant for skipping bail. Sweden dropped the investigation against Assange in 2017, although Swedish prosecutors indicated it may be resumed if Assange "makes himself

Assange argued that his avoidance of European law enforcement was necessary to protect him from extradition to the US, where then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said that arresting him is a "priority." WikiLeaks was branded a "non-state hostile intelligence service" by then-CIA head Mike Pompeo in 2017.

The US government has been tight-lipped on whether Assange would face indictment over the dissemination of classified material. In November 2018, the existence of a secret indictment targeting Assange was seemingly unintentionally confirmed in a US court filing for an unrelated case.

Last year, a UK tribunal refused to release key details on communications between British and Swedish authorities that could have revealed any dealings between the UK, Sweden, the US, and Ecuador in the long-running Assange debacle. La Repubblica journalist Stefania Maurizi had her appeal to obtain documents held by the Crown Prosecution Service dismissed on December 12.

WikiLeaks is responsible for publishing thousands of documents with sensitive information from many countries. Those include the 2003 Standard Operating Procedures manual for Guantanamo Bay, the controversial detention center in Cuba. The agency has also released documents on Scientology, one tranche referred to as "secret bibles" from the religion founded by L. Ron Hubbard.

https://www.rt.com/news/456212-julian-a ... -eviction/

Welcome To Roj Bash Kurdistan

Julian Assange FREED after crucifixion for telling the truth

24 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Julian Assange FREED after crucifixion for telling the truth

Last edited by Anthea on Sat Jan 09, 2021 7:35 pm, edited 2 times in total.

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 29418

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: End of free speech WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange arre

Charging Julian Assange With Espionage Could Make His Extradition to the U.S. Less Likely

By charging Julian Assange with 17 violations of America’s World War I-era Espionage Act on Thursday, federal prosecutors in Virginia might have undermined their own chances of securing the extradition of the WikiLeaks founder from the United Kingdom

That’s because the new charges relate not to any arcane interpretation of computer hacking laws, but to WikiLeaks’ publication of hundreds of thousands of American military reports and diplomatic cables provided by the former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning in 2010.

The fact that WikiLeaks published many of those documents in collaboration with an international consortium of leading news organizations — including The Guardian, the New York Times, Le Monde, El País, and Der Spiegel — ensured that the charges against Assange were immediately denounced by journalists and free speech advocates as an unconstitutional assault on press freedom guaranteed by the First Amendment.

That would make his transfer to Virginia at the end of his jail term in London unlawful, since Article 4 of the U.S.-U.K. extradition treaty, signed in 2003, clearly states that “extradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense.”

In what could be an attempt by prosecutors to distinguish Assange’s publication of those documents from their use by news organizations, the indictment focuses on cases in which WikiLeaks published military intelligence files that were not redacted to remove the names of Iraqis and Afghans who had provided information to U.S. forces.

Declan Walsh, who was The Guardian’s Pakistan correspondent at the time, recalled that Assange was indifferent to the harm he might cause by revealing those names, but, as the journalist Alexa O’Brien has reported, there appears to be no evidence that any of those individuals were killed as a result of the online disclosures.

British authorities are already faced with a competing extradition request from Sweden, where prosecutors have reopened an investigation of Assange for rape in response to a complaint filed in 2010. That case has already been adjudicated in England’s High Court. After Assange lost his final appeal against extradition to Sweden in 2012, he took refuge in Ecuador’s Embassy in London, where he lived until his asylum was revoked this year.

A British judge will issue a preliminary decision on whether to grant priority to the Swedish request or the American one, but the ultimate decision on Assange’s extradition will be made by a politician, the U.K. home secretary.

That process could be intensely political, given that Prime Minister Theresa May announced her imminent resignation on Friday, and one of the leading contenders to replace her is Sajid Javid, the current home secretary.

The disarray in Britain over the country’s stalled exit from the European Union could incline Javid, or his successor at the Home Office, to seek closer ties with the U.S. and expedited trade talks with U.S. President Donald Trump by sending Assange there, but there is also pressure on Javid to consider the Swedish request seriously in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

Last month, more than 70 British lawmakers signed a letter to Javid from Stella Creasy, a member of Parliament for the opposition Labour Party, urging him to give priority to an extradition request from Sweden. “We must send a strong message of the priority the U.K. has in tackling sexual violence and the seriousness with which such allegations are viewed,” Creasy wrote. “We urge you to stand with the victims of sexual violence and seek to ensure the case against Mr. Assange can now be properly investigated.”

That view was echoed on Friday by Christian Christensen, a professor of journalism at Stockholm University.

By charging Julian Assange with 17 violations of America’s World War I-era Espionage Act on Thursday, federal prosecutors in Virginia might have undermined their own chances of securing the extradition of the WikiLeaks founder from the United Kingdom

That’s because the new charges relate not to any arcane interpretation of computer hacking laws, but to WikiLeaks’ publication of hundreds of thousands of American military reports and diplomatic cables provided by the former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning in 2010.

The fact that WikiLeaks published many of those documents in collaboration with an international consortium of leading news organizations — including The Guardian, the New York Times, Le Monde, El País, and Der Spiegel — ensured that the charges against Assange were immediately denounced by journalists and free speech advocates as an unconstitutional assault on press freedom guaranteed by the First Amendment.

- Assange's motives or membership in an undefinable "journalist" club are irrelevant to the very dangerous step that the Trump DOJ took today. We'll now find out whether *publishing* information (as well as seeking and obtaining it) may constitutionally be charged as espionage.

— Barton Gellman (@bartongellman) May 23, 2019

- When you read Demers' quote, please remember that the President of the United States has repeatedly referred to the New York Times as "the enemy of the people." Do we really want Trump's Justice Department deciding who is and who is not a "journalist"? https://t.co/aaV8YfECAw

— Elizabeth Goitein (@LizaGoitein) May 23, 2019

That would make his transfer to Virginia at the end of his jail term in London unlawful, since Article 4 of the U.S.-U.K. extradition treaty, signed in 2003, clearly states that “extradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense.”

In what could be an attempt by prosecutors to distinguish Assange’s publication of those documents from their use by news organizations, the indictment focuses on cases in which WikiLeaks published military intelligence files that were not redacted to remove the names of Iraqis and Afghans who had provided information to U.S. forces.

Declan Walsh, who was The Guardian’s Pakistan correspondent at the time, recalled that Assange was indifferent to the harm he might cause by revealing those names, but, as the journalist Alexa O’Brien has reported, there appears to be no evidence that any of those individuals were killed as a result of the online disclosures.

British authorities are already faced with a competing extradition request from Sweden, where prosecutors have reopened an investigation of Assange for rape in response to a complaint filed in 2010. That case has already been adjudicated in England’s High Court. After Assange lost his final appeal against extradition to Sweden in 2012, he took refuge in Ecuador’s Embassy in London, where he lived until his asylum was revoked this year.

A British judge will issue a preliminary decision on whether to grant priority to the Swedish request or the American one, but the ultimate decision on Assange’s extradition will be made by a politician, the U.K. home secretary.

That process could be intensely political, given that Prime Minister Theresa May announced her imminent resignation on Friday, and one of the leading contenders to replace her is Sajid Javid, the current home secretary.

The disarray in Britain over the country’s stalled exit from the European Union could incline Javid, or his successor at the Home Office, to seek closer ties with the U.S. and expedited trade talks with U.S. President Donald Trump by sending Assange there, but there is also pressure on Javid to consider the Swedish request seriously in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

Last month, more than 70 British lawmakers signed a letter to Javid from Stella Creasy, a member of Parliament for the opposition Labour Party, urging him to give priority to an extradition request from Sweden. “We must send a strong message of the priority the U.K. has in tackling sexual violence and the seriousness with which such allegations are viewed,” Creasy wrote. “We urge you to stand with the victims of sexual violence and seek to ensure the case against Mr. Assange can now be properly investigated.”

That view was echoed on Friday by Christian Christensen, a professor of journalism at Stockholm University.

- Espionage charges against #Assange are an attack on a free press. He should still be sent to Sweden.

— Christian Christensen (@ChrChristensen) May 24, 2019

- For the record. I think it was reasonable, legal and desirable for Assange to be surrendered to Sweden to face rape allegations, the same does not necessarily apply when it comes to a surrender to the US since it essentially concerns (potentially) political crimes.

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 29418

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: End of free speech as Julian Assange faces 17 more charg

The crucifixion of Julian Assange

By Jomo Sanga Thomas

“WikiLeaks and you personally are facing a battle that is both legal and political. As we learned in the Pentagon Papers case, the US government doesn’t like the truth coming out. And it doesn’t like to be humiliated. No matter if it’s Nixon or Bush or Obama or Trump, Republican or Democrat in the White House. The US government will try to stop you from publishing its ugly secrets. And if they have to destroy you and the First Amendment and the rights of publishers with you, they are willing to do it. We believe they are going to come after WikiLeaks and you, Julian, as the publisher.” — Len Weinglass, US human rights lawyer.

“The Assange’s arrest eviscerates all pretense of the rule of law and the rights of a free press. The illegalities, embraced by the Ecuadorian, British and US governments, in the seizure of Assange were ominous. They presaged a world where the internal workings, abuses, corruption, lies and crimes — especially war crimes — carried out by corporate states and the global ruling elite will be masked from the public. They presaged a world where those with the courage and integrity to expose the misuse of power will be hunted down, tortured, subjected to sham trials and given lifetime prison terms in solitary confinement. They presaged an Orwellian dystopia where news is replaced with propaganda, trivia and entertainment.” — Chris Hedges.

The decision by a British high court judge to deny the Trump regime’s extradition request to extradite to the United States, Wikileaks publisher, Julian Assange, is a major victory for press freedom and the rule of law. Alluding to the US prison system’s horrendous nature, the judge ruled that to extradite Assange would be oppressive because of mental harm. She feared the prison conditions might lead Assange to commit suicide.

On Wednesday, the judge refused Assange’s application for bail while he awaits the US Government’s appeal. Assange will remain in the British prison even after the UN Human Rights Rapporteur’s revelation that Assange’s treatment amounts to torture, which is illegal under international human rights law. The decision to deny bail to Assange is both cruel and inhumane. There is no pending charge in Britain against the WikiLeaks publisher.

Assange’s trouble began 10 years ago after WikiLeaks released the Iraq War Logs which documented numerous US war crimes — including video images of the gunning down of two Reuters journalists and 10 other unarmed civilians, the routine torture of Iraqi prisoners, the covering up of thousands of civilian deaths and the killing of nearly 700 civilians that approached US checkpoints.

First, they tried to smear him with sexual assault/rape charges. One of the women said, “I did not want to put any charges on Julian Assange, but the police were keen on getting their hands on him … I felt railroaded by the police.” The chief prosecutor of Stockholm dropped the rape accusation concluding, “I don’t believe there is any reason to suspect that he has committed rape.” Yet, a special prosecutor was appointed to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct.

Assange is charged with violating 17 counts of the Espionage Act, along with an attempt to hack into a government computer. If extradited, tried and convicted, he could face as much as 175 years in prison.

Ominously, the judge accepted all of the charges levelled by the US against Assange — that he violated the Espionage Act by releasing classified information and was complicit in assisting his source, Chelsea Manning, in the hacking of a government computer.

If the appellate court overrules the decision to deny extradition, it will be a very dangerous ruling for the media. The publication of classified documents is not yet a crime in the United States. Bob Woodward of the Washington Post has made a career publishing establishment secrets. However, if Assange is extradited and convicted, it will become a crime to publish classified information.

According to Chris Hedges, “The extradition of Assange would mean the end of journalistic investigations into the inner workings of power. It would cement into place a terrifying global, corporate tyranny under which borders, nationality and law mean nothing. Once such a legal precedent is set, any publication that publishes classified material, from The New York Times to an alternative website, will be prosecuted and silenced … Journalists can argue that this information, like the war logs, should have remained hidden, but they can’t then call themselves journalists.”

Make no mistake, Julian Assange has done more than any contemporary journalist or publisher to expose the inner workings of the US government, and the lies and crimes of the US ruling elite. This fact explains the deep hatred towards Assange.

The Democrats despise Assange because WikiLeaks exposed emails from John Podesta’s account, Hilary Clinton’s campaign manager. They exposed Clinton as a deceitful pathological liar. The emails exposed her telling the financial elites that she wanted “open trade and open borders” and wanted Wall Street executives to manage the economy, a statement that contradicted her campaign statements. They exposed the Clinton campaign’s efforts to influence the Republican primaries to ensure that Donald Trump was the Republican nominee. They exposed Clinton’s advance knowledge of questions in a primary debate. They exposed Clinton as the principal architect of the war in Libya, thus turning Africa’s second most-developed country into a failed state.

Among the documents WikiLeaks released were cables from US embassies. Assange’s lawyer, Michael Ratner said the cables “pulled back the curtain and revealed American foreign policy behind-the-scenes manipulations”. Some of the most stunning revelations:

* In 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton ordered US diplomats to spy on UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon and other UN representatives from China, France, Russia, and the UK. The US and British diplomats also eavesdropped on UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan before the US-led Iraq invasion in 2003.

* President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton refused to condemn the June 2009 military coup in Honduras after American diplomats described the coup as “illegal and unconstitutional”.

As a journalist and publisher of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange had every right to asylum. The law is clear. The exercise of political free speech — including revealing government crimes, misconduct, or corruption — is internationally protected and is grounds for asylum.

Democracy dies in the dark. Julian Assange should be freed. His only crime is his courageous effort to expose the lies, crimes and deceit of the ruling elite

https://www.iwnsvg.com/2021/01/08/the-c ... n-assange/

By Jomo Sanga Thomas

“WikiLeaks and you personally are facing a battle that is both legal and political. As we learned in the Pentagon Papers case, the US government doesn’t like the truth coming out. And it doesn’t like to be humiliated. No matter if it’s Nixon or Bush or Obama or Trump, Republican or Democrat in the White House. The US government will try to stop you from publishing its ugly secrets. And if they have to destroy you and the First Amendment and the rights of publishers with you, they are willing to do it. We believe they are going to come after WikiLeaks and you, Julian, as the publisher.” — Len Weinglass, US human rights lawyer.

“The Assange’s arrest eviscerates all pretense of the rule of law and the rights of a free press. The illegalities, embraced by the Ecuadorian, British and US governments, in the seizure of Assange were ominous. They presaged a world where the internal workings, abuses, corruption, lies and crimes — especially war crimes — carried out by corporate states and the global ruling elite will be masked from the public. They presaged a world where those with the courage and integrity to expose the misuse of power will be hunted down, tortured, subjected to sham trials and given lifetime prison terms in solitary confinement. They presaged an Orwellian dystopia where news is replaced with propaganda, trivia and entertainment.” — Chris Hedges.

The decision by a British high court judge to deny the Trump regime’s extradition request to extradite to the United States, Wikileaks publisher, Julian Assange, is a major victory for press freedom and the rule of law. Alluding to the US prison system’s horrendous nature, the judge ruled that to extradite Assange would be oppressive because of mental harm. She feared the prison conditions might lead Assange to commit suicide.

On Wednesday, the judge refused Assange’s application for bail while he awaits the US Government’s appeal. Assange will remain in the British prison even after the UN Human Rights Rapporteur’s revelation that Assange’s treatment amounts to torture, which is illegal under international human rights law. The decision to deny bail to Assange is both cruel and inhumane. There is no pending charge in Britain against the WikiLeaks publisher.

Assange’s trouble began 10 years ago after WikiLeaks released the Iraq War Logs which documented numerous US war crimes — including video images of the gunning down of two Reuters journalists and 10 other unarmed civilians, the routine torture of Iraqi prisoners, the covering up of thousands of civilian deaths and the killing of nearly 700 civilians that approached US checkpoints.

First, they tried to smear him with sexual assault/rape charges. One of the women said, “I did not want to put any charges on Julian Assange, but the police were keen on getting their hands on him … I felt railroaded by the police.” The chief prosecutor of Stockholm dropped the rape accusation concluding, “I don’t believe there is any reason to suspect that he has committed rape.” Yet, a special prosecutor was appointed to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct.

Assange is charged with violating 17 counts of the Espionage Act, along with an attempt to hack into a government computer. If extradited, tried and convicted, he could face as much as 175 years in prison.

Ominously, the judge accepted all of the charges levelled by the US against Assange — that he violated the Espionage Act by releasing classified information and was complicit in assisting his source, Chelsea Manning, in the hacking of a government computer.

If the appellate court overrules the decision to deny extradition, it will be a very dangerous ruling for the media. The publication of classified documents is not yet a crime in the United States. Bob Woodward of the Washington Post has made a career publishing establishment secrets. However, if Assange is extradited and convicted, it will become a crime to publish classified information.

According to Chris Hedges, “The extradition of Assange would mean the end of journalistic investigations into the inner workings of power. It would cement into place a terrifying global, corporate tyranny under which borders, nationality and law mean nothing. Once such a legal precedent is set, any publication that publishes classified material, from The New York Times to an alternative website, will be prosecuted and silenced … Journalists can argue that this information, like the war logs, should have remained hidden, but they can’t then call themselves journalists.”

Make no mistake, Julian Assange has done more than any contemporary journalist or publisher to expose the inner workings of the US government, and the lies and crimes of the US ruling elite. This fact explains the deep hatred towards Assange.

The Democrats despise Assange because WikiLeaks exposed emails from John Podesta’s account, Hilary Clinton’s campaign manager. They exposed Clinton as a deceitful pathological liar. The emails exposed her telling the financial elites that she wanted “open trade and open borders” and wanted Wall Street executives to manage the economy, a statement that contradicted her campaign statements. They exposed the Clinton campaign’s efforts to influence the Republican primaries to ensure that Donald Trump was the Republican nominee. They exposed Clinton’s advance knowledge of questions in a primary debate. They exposed Clinton as the principal architect of the war in Libya, thus turning Africa’s second most-developed country into a failed state.

Among the documents WikiLeaks released were cables from US embassies. Assange’s lawyer, Michael Ratner said the cables “pulled back the curtain and revealed American foreign policy behind-the-scenes manipulations”. Some of the most stunning revelations:

* In 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton ordered US diplomats to spy on UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon and other UN representatives from China, France, Russia, and the UK. The US and British diplomats also eavesdropped on UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan before the US-led Iraq invasion in 2003.

* President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton refused to condemn the June 2009 military coup in Honduras after American diplomats described the coup as “illegal and unconstitutional”.

As a journalist and publisher of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange had every right to asylum. The law is clear. The exercise of political free speech — including revealing government crimes, misconduct, or corruption — is internationally protected and is grounds for asylum.

Democracy dies in the dark. Julian Assange should be freed. His only crime is his courageous effort to expose the lies, crimes and deceit of the ruling elite

https://www.iwnsvg.com/2021/01/08/the-c ... n-assange/

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 29418

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Free Speech Ended With Illegal crucifixion of Julian Ass

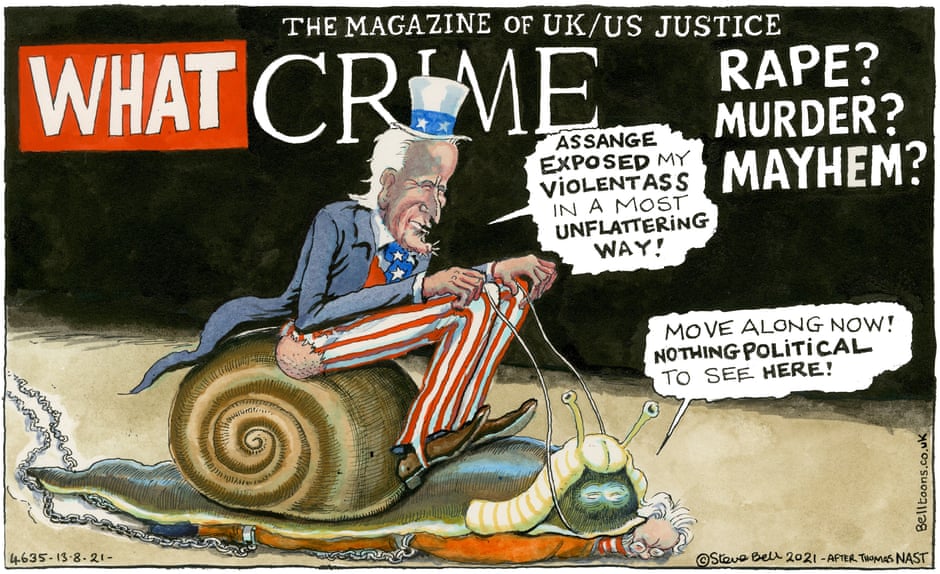

Steve Bell on a UK judge backing the US appeal in Julian Assange’s extradition case

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 29418

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Free Speech Ended With Illegal crucifixion of Julian Ass

Julian Assange loses court battle

The WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, has lost a high court battle to prevent the US government expanding the grounds for its appeal against an earlier refusal to allow his extradition to face charges of espionage and hacking government computers

On Wednesday, judges said the weight given to a misleading report from Assange’s psychiatric expert that was submitted at the original hearing in January could form part of Washington’s full appeal in October.

Sitting in London, Lord Justice Holroyde said he believed it was arguable that Judge Vanessa Baraitser had attached too much weight to the evidence of Prof Michael Kopelman when deciding not to allow the US’s appeal.

The expert had told the court he believed Assange would take his own life if extradited. But he did not include in his report the fact that Assange had fathered two children with his partner while holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London – a fact Assange later used in support of his bail application.

Clair Dobbin QC, for the US, argued the expert misled Baraitser, who presided over the January hearing.

Edward Fitzgerald QC, representing Assange, told the court Baraitser, having heard all of the evidence in the case, was in the best position to assess it and reach her decision.

He said Kopelman’s report was given long before any court hearing and against a background of concern for the “human predicament” in which Assange’s partner, Stella Moris, found herself at the time.

Delivering the latest decision, Holroyde said it was “very unusual” for an appeal court to have to consider evidence from an expert that had been accepted by a lower court, but also found to have been misleading – even if the expert’s actions had been deemed an “understandable human response” designed to protect the privacy of Assange’s partner and children.

The judge said that, in those circumstances, it was “at least arguable” that Baraitser erred in basing her conclusions on the professor’s evidence.

“Given the importance to the administration of justice of a court being able to reply on the impartiality of an expert witness, it is in my view arguable that more detailed and critical consideration should have been given to why [the professor’s] ‘understandable human response’ gave rise to a misleading report.”

The US government had previously been allowed to appeal against Baraitser’s decision on three grounds – including that it was wrong in law. Assange’s legal team had described the grounds as “narrow” and “technical”. The two allowed on Wednesday were additional.

During Wednesday’s hearing, the US government argued Assange, 50, was not “so ill” that he would be unable to resist killing himself if extradited – challenging Baraitser’s ruling that the US authorities could not “prevent Assange from finding a way to commit suicide” if he was extradited.

Dobbin said the US government would seek to show that Assange’s mental health problems did not meet the threshold required in law to prevent extradition.

She told the court: “It really requires a mental illness of a type that the ability to resist suicide has been lost. Part of the appeal will be that Assange did not have a mental illness that came close to being of that nature and degree.”

Holroyde said he would not ordinarily have allowed this to form part of the appeal on its own merits alone. But he said it must be taken in the context of the broader grounds allowed and could be argued at the full hearing.

Assange appeared at the hearing via video link from Belmarsh prison, wearing a dark face covering and a white shirt, with what appeared to be an untied burgundy tie draped around his neck.

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/ ... ion-appeal

The WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, has lost a high court battle to prevent the US government expanding the grounds for its appeal against an earlier refusal to allow his extradition to face charges of espionage and hacking government computers

On Wednesday, judges said the weight given to a misleading report from Assange’s psychiatric expert that was submitted at the original hearing in January could form part of Washington’s full appeal in October.

Sitting in London, Lord Justice Holroyde said he believed it was arguable that Judge Vanessa Baraitser had attached too much weight to the evidence of Prof Michael Kopelman when deciding not to allow the US’s appeal.

The expert had told the court he believed Assange would take his own life if extradited. But he did not include in his report the fact that Assange had fathered two children with his partner while holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London – a fact Assange later used in support of his bail application.

Clair Dobbin QC, for the US, argued the expert misled Baraitser, who presided over the January hearing.

Edward Fitzgerald QC, representing Assange, told the court Baraitser, having heard all of the evidence in the case, was in the best position to assess it and reach her decision.

He said Kopelman’s report was given long before any court hearing and against a background of concern for the “human predicament” in which Assange’s partner, Stella Moris, found herself at the time.

Delivering the latest decision, Holroyde said it was “very unusual” for an appeal court to have to consider evidence from an expert that had been accepted by a lower court, but also found to have been misleading – even if the expert’s actions had been deemed an “understandable human response” designed to protect the privacy of Assange’s partner and children.

The judge said that, in those circumstances, it was “at least arguable” that Baraitser erred in basing her conclusions on the professor’s evidence.

“Given the importance to the administration of justice of a court being able to reply on the impartiality of an expert witness, it is in my view arguable that more detailed and critical consideration should have been given to why [the professor’s] ‘understandable human response’ gave rise to a misleading report.”

The US government had previously been allowed to appeal against Baraitser’s decision on three grounds – including that it was wrong in law. Assange’s legal team had described the grounds as “narrow” and “technical”. The two allowed on Wednesday were additional.

During Wednesday’s hearing, the US government argued Assange, 50, was not “so ill” that he would be unable to resist killing himself if extradited – challenging Baraitser’s ruling that the US authorities could not “prevent Assange from finding a way to commit suicide” if he was extradited.

Dobbin said the US government would seek to show that Assange’s mental health problems did not meet the threshold required in law to prevent extradition.

She told the court: “It really requires a mental illness of a type that the ability to resist suicide has been lost. Part of the appeal will be that Assange did not have a mental illness that came close to being of that nature and degree.”

Holroyde said he would not ordinarily have allowed this to form part of the appeal on its own merits alone. But he said it must be taken in the context of the broader grounds allowed and could be argued at the full hearing.

Assange appeared at the hearing via video link from Belmarsh prison, wearing a dark face covering and a white shirt, with what appeared to be an untied burgundy tie draped around his neck.

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/ ... ion-appeal

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 29418

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Free Speech Ended With Illegal crucifixion of Julian Ass

CIA plotted to kidnap Julian Assange

Kidnapping, assassination and a London shoot-out: Inside the CIA's secret war plans against WikiLeaks

In 2017, as Julian Assange began his fifth year holed up in Ecuador’s embassy in London, the CIA plotted to kidnap the WikiLeaks founder, spurring heated debate among Trump administration officials over the legality and practicality of such an operation.

Some senior officials inside the CIA and the Trump administration even discussed killing Assange, going so far as to request “sketches” or “options” for how to assassinate him. Discussions over kidnapping or killing Assange occurred “at the highest levels” of the Trump administration, said a former senior counterintelligence official. “There seemed to be no boundaries.”

The conversations were part of an unprecedented CIA campaign directed against WikiLeaks and its founder. The agency’s multipronged plans also included extensive spying on WikiLeaks associates, sowing discord among the group’s members, and stealing their electronic devices.

While Assange had been on the radar of U.S. intelligence agencies for years, these plans for an all-out war against him were sparked by WikiLeaks’ ongoing publication of extraordinarily sensitive CIA hacking tools, known collectively as “Vault 7,” which the agency ultimately concluded represented “the largest data loss in CIA history.”

President Trump’s newly installed CIA director, Mike Pompeo, was seeking revenge on WikiLeaks and Assange, who had sought refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy since 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden on rape allegations he denied. Pompeo and other top agency leaders “were completely detached from reality because they were so embarrassed about Vault 7,” said a former Trump national security official. “They were seeing blood.”

Michael Pompeo, director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), listens during a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Thursday, May 11, 2017. ( Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The CIA’s fury at WikiLeaks led Pompeo to publicly describe the group in 2017 as a “non-state hostile intelligence service.” More than just a provocative talking point, the designation opened the door for agency operatives to take far more aggressive actions, treating the organization as it does adversary spy services, former intelligence officials told Yahoo News. Within months, U.S. spies were monitoring the communications and movements of numerous WikiLeaks personnel, including audio and visual surveillance of Assange himself, according to former officials.

This Yahoo News investigation, based on conversations with more than 30 former U.S. officials — eight of whom described details of the CIA’s proposals to abduct Assange — reveals for the first time one of the most contentious intelligence debates of the Trump presidency and exposes new details about the U.S. government’s war on WikiLeaks. It was a campaign spearheaded by Pompeo that bent important legal strictures, potentially jeopardized the Justice Department’s work toward prosecuting Assange, and risked a damaging episode in the United Kingdom, the United States’ closest ally.

The CIA declined to comment. Pompeo did not respond to requests for comment.

“As an American citizen, I find it absolutely outrageous that our government would be contemplating kidnapping or assassinating somebody without any judicial process simply because he had published truthful information,” Barry Pollack, Assange’s U.S. lawyer, told Yahoo News.

Assange is now housed in a London prison as the courts there decide on a U.S. request to extradite the WikiLeaks founder on charges of attempting to help former U.S. Army analyst Chelsea Manning break into a classified computer network and conspiring to obtain and publish classified documents in violation of the Espionage Act.

“My hope and expectation is that the U.K. courts will consider this information and it will further bolster its decision not to extradite to the U.S.,” Pollack added.

There is no indication that the most extreme measures targeting Assange were ever approved, in part because of objections from White House lawyers, but the agency’s WikiLeaks proposals so worried some administration officials that they quietly reached out to staffers and members of Congress on the House and Senate intelligence committees to alert them to what Pompeo was suggesting. “There were serious intel oversight concerns that were being raised through this escapade,” said a Trump national security official.

Some National Security Council officials worried that the CIA’s proposals to kidnap Assange would not only be illegal but also might jeopardize the prosecution of the WikiLeaks founder. Concerned the CIA’s plans would derail a potential criminal case, the Justice Department expedited the drafting of charges against Assange to ensure that they were in place if he were brought to the United States.

In late 2017, in the midst of the debate over kidnapping and other extreme measures, the agency’s plans were upended when U.S. officials picked up what they viewed as alarming reports that Russian intelligence operatives were preparing to sneak Assange out of the United Kingdom and spirit him away to Moscow.

The intelligence reporting about a possible breakout was viewed as credible at the highest levels of the U.S. government. At the time, Ecuadorian officials had begun efforts to grant Assange diplomatic status as part of a scheme to give him cover to leave the embassy and fly to Moscow to serve in the country’s Russian mission.

In response, the CIA and the White House began preparing for a number of scenarios to foil Assange’s Russian departure plans, according to three former officials. Those included potential gun battles with Kremlin operatives on the streets of London, crashing a car into a Russian diplomatic vehicle transporting Assange and then grabbing him, and shooting out the tires of a Russian plane carrying Assange before it could take off for Moscow. (U.S. officials asked their British counterparts to do the shooting if gunfire was required, and the British agreed, according to a former senior administration official.)

“We had all sorts of reasons to believe he was contemplating getting the hell out of there,” said the former senior administration official, adding that one report said Assange might try to escape the embassy hidden in a laundry cart. “It was going to be like a prison break movie.”

The intrigue over a potential Assange escape set off a wild scramble among rival spy services in London. American, British and Russian agencies, among others, stationed undercover operatives around the Ecuadorian Embassy. In the Russians’ case, it was to facilitate a breakout. For the U.S. and allied services, it was to block such an escape. “It was beyond comical,” said the former senior official. “It got to the point where every human being in a three-block radius was working for one of the intelligence services — whether they were street sweepers or police officers or security guards.”

White House officials briefed Trump and warned him that the matter could provoke an international incident — or worse. “We told him, this is going to get ugly,” said the former official.

As the debate over WikiLeaks intensified, some in the White House worried that the campaign against the organization would end up “weakening America,” as one Trump national security official put it, by lowering barriers that prevent the government from targeting mainstream journalists and news organizations, said former officials.

The fear at the National Security Council, the former official said, could be summed up as, “Where does this stop?”

When WikiLeaks launched its website in December 2006, it was a nearly unprecedented model: Anyone anywhere could submit materials anonymously for publication. And they did, on topics ranging from secret fraternity rites to details of the U.S. government’s Guantánamo Bay detainee operations.

Yet Assange, the lanky Australian activist who led the organization, didn’t get much attention until 2010, when WikiLeaks released gun camera footage of a 2007 airstrike by U.S. Army helicopters in Baghdad that killed at least a dozen people, including two Reuters journalists, and wounded two young children. The Pentagon had refused to release the dramatic video, but someone had provided it to WikiLeaks.

Wikileaks releases leaked 2007 footage of a U.S. Apache helicopter fatally shooting a group of men at public square in Eastern Baghdad. (U.S. Military via Wikileaks.org)

Later that year, WikiLeaks also published several caches of classified and sensitive U.S. government documents related to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as more than 250,000 U.S. diplomatic cables. Assange was hailed in some circles as a hero and in others as a villain. For U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies, the question was how to deal with the group, which operated differently than typical news outlets. “The problem posed by WikiLeaks was, there wasn’t anything like it,” said a former intelligence official.

How to define WikiLeaks has long confounded everyone from government officials to press advocates. Some view it as an independent journalistic institution, while others have asserted it is a handmaiden to foreign spy services.

“They’re not a journalistic organization, they’re nowhere near it,” William Evanina, who retired as the U.S.’s top counterintelligence official in early 2021, told Yahoo News in an interview. Evanina declined to discuss specific U.S. proposals regarding Assange or WikiLeaks.

But the Obama administration, fearful of the consequences for press freedom — and chastened by the blowback from its own aggressive leak hunts — restricted investigations into Assange and WikiLeaks. “We were stagnated for years,” said Evanina. “There was a reticence in the Obama administration at a high level to allow agencies to engage in” certain kinds of intelligence collection against WikiLeaks, including signals and cyber operations, he said.

That began to change in 2013, when Edward Snowden, a National Security Agency contractor, fled to Hong Kong with a massive trove of classified materials, some of which revealed that the U.S. government was illegally spying on Americans. WikiLeaks helped arrange Snowden’s escape to Russia from Hong Kong. A WikiLeaks editor also accompanied Snowden to Russia, staying with him during his 39-day enforced stay at a Moscow airport and living with him for three months after Russia granted Snowden asylum.

In the wake of the Snowden revelations, the Obama administration allowed the intelligence community to prioritize collection on WikiLeaks, according to Evanina, now the CEO of the Evanina Group. Previously, if the FBI needed a search warrant to go into the group’s databases in the United States or wanted to use subpoena power or a national security letter to gain access to WikiLeaks-related financial records, “that wasn’t going to happen,” another former senior counterintelligence official said. “That changed after 2013.”

U.S. whistle-blower Edward Snowden is displayed on a giant screen during a local news program in Hong Kong, China on June 23, 2013. The Hong Kong government has confirmed that Edward Snowden has left Hong Kong and is on a commercial flight to Russia. (Sam Tsang/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

From that point onward, U.S. intelligence worked closely with friendly spy agencies to build a picture of WikiLeaks’ network of contacts “and tie it back to hostile state intelligence services,” Evanina said. The CIA assembled a group of analysts known unofficially as “the WikiLeaks team” in its Office of Transnational Issues, with a mission to examine the organization, according to a former agency official.

Still chafing at the limits in place, top intelligence officials lobbied the White House to redefine WikiLeaks — and some high-profile journalists — as “information brokers,” which would have opened up the use of more investigative tools against them, potentially paving the way for their prosecution, according to former officials. It “was a step in the direction of showing a court, if we got that far, that we were dealing with agents of a foreign power,” a former senior counterintelligence official said.

Among the journalists some U.S. officials wanted to designate as “information brokers” were Glenn Greenwald, then a columnist for the Guardian, and Laura Poitras, a documentary filmmaker, who had both been instrumental in publishing documents provided by Snowden.

“Is WikiLeaks a journalistic outlet? Are Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald truly journalists?” the former official said. “We tried to change the definition of them, and I preached this to the White House, and got rejected.”

The Obama administration’s policy was, “If there’s published works out there, doesn’t matter the venue, then we have to treat them as First-Amendment-protected individuals,” the former senior counterintelligence official said. “There were some exceptions to that rule, but they were very, very, very few and far between.” WikiLeaks, the administration decided, did not fit that exception.

In a statement to Yahoo News, Poitras said reported attempts to classify herself, Greenwald and Assange as “information brokers” rather than journalists are “bone-chilling and a threat to journalists worldwide.”

“That the CIA also conspired to seek the rendition and extrajudicial assassination of Julian Assange is a state-sponsored crime against the press,” she added.

“I am not the least bit surprised that the CIA, a longtime authoritarian and antidemocratic institution, plotted to find a way to criminalize journalism and spy on and commit other acts of aggression against journalists,” Greenwald told Yahoo News.

By 2015, WikiLeaks was the subject of an intense debate over whether the organization should be targeted by law enforcement or spy agencies. Some argued that the FBI should have sole responsibility for investigating WikiLeaks, with no role for the CIA or the NSA. The Justice Department, in particular, was “very protective” of its authorities over whether to charge Assange and whether to treat WikiLeaks “like a media outlet,” said Robert Litt, the intelligence community’s senior lawyer during the Obama administration.

Then, in the summer of 2016, at the height of the presidential election season, came a seismic episode in the U.S. government’s evolving approach to WikiLeaks, when the website began publishing Democratic Party emails. The U.S. intelligence community later concluded the Russian military intelligence agency known as the GRU had hacked the emails.

In response to the leak, the NSA began surveilling the Twitter accounts of the suspected Russian intelligence operatives who were disseminating the leaked Democratic Party emails, according to a former CIA official. This collection revealed direct messages between the operatives, who went by the moniker Guccifer 2.0, and WikiLeaks’ Twitter account. Assange at the time steadfastly denied that the Russian government was the source for the emails, which were also published by mainstream news organizations.

Even so, Assange’s communication with the suspected operatives settled the matter for some U.S. officials. The events of 2016 “really crystallized” U.S. intelligence officials’ belief that the WikiLeaks founder “was acting in collusion with people who were using him to hurt the interests of the United States,” said Litt.

After the publication of the Democratic Party emails, there was “zero debate” on the issue of whether the CIA would increase its spying on WikiLeaks, said a former intelligence official. But there was still “sensitivity on how we would collect on them,” the former official added.

The CIA now considered people affiliated with WikiLeaks valid targets for various types of spying, including close-in technical collection — such as bugs — sometimes enabled by in-person espionage, and “remote operations,” meaning, among other things, the hacking of WikiLeaks members’ devices from afar, according to former intelligence officials.

The Obama administration’s view of WikiLeaks underwent what Evanina described as a “sea change” shortly before Donald Trump, helped in part by WikiLeaks’ release of Democratic campaign emails, won a surprise victory over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election.

As Trump’s national security team took their positions at the Justice Department and the CIA, officials wondered whether, despite his campaign trail declaration of “love” for WikiLeaks, Trump’s appointees would take a more hard-line view of the organization. They were not to be disappointed.

“There was a fundamental change on how [WikiLeaks was] viewed,” said a former senior counterintelligence official. When it came to prosecuting Assange — something the Obama administration had declined to do — the Trump White House had a different approach, said a former Justice Department official. “Nobody in that crew was going to be too broken up about the First Amendment issues.”

On April 13, 2017, wearing a U.S. flag pin on the left lapel of his dark gray suit, Pompeo strode to the podium at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington think tank, to deliver to a standing-room-only crowd his first public remarks as Trump’s CIA director.

Rather than use the platform to give an overview of global challenges or to lay out any bureaucratic changes he was planning to make at the agency, Pompeo devoted much of his speech to the threat posed by WikiLeaks.

“WikiLeaks walks like a hostile intelligence service and talks like a hostile intelligence service and has encouraged its followers to find jobs at the CIA in order to obtain intelligence,” he said.

“It’s time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is: a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia,” he continued.

It had been barely five weeks since WikiLeaks had stunned the CIA when it announced it had obtained a massive tranche of files — which it dubbed “Vault 7” — from the CIA’s ultrasecret hacking division. Despite the CIA’s ramped up collection on WikiLeaks, the announcement came as a complete surprise to the agency, but as soon as the organization posted the first materials on its website, the CIA knew it was facing a catastrophe.

Vault 7 “hurt the agency to its core,” said a former CIA official. Agency officials “used to laugh about WikiLeaks,” mocking the State Department and the Pentagon for allowing so much material to escape their control.

Pompeo, apparently fearful of the president’s wrath, was initially reluctant to even brief the president on Vault 7, according to a former senior Trump administration official. “Don’t tell him, he doesn’t need to know,” Pompeo told one briefer, before being advised that the information was too critical and the president had to be informed, said the former official.

Irate senior FBI and NSA officials repeatedly demanded interagency meetings to determine the scope of the damage caused by Vault 7, according to another former national security official.

The NSA believed that, although the leak revealed only CIA hacking operations, it could also give countries like Russia or China clues about NSA targets and methods, said this former official.

Pompeo’s aggressive tone at CSIS reflected his “brash attitude,” said a former senior intelligence official. “He would want to push the limits as much as he could” during his tenure as CIA director, the former official said.

The Trump administration was sending more signals that it would no longer be bound by the Obama administration’s self-imposed restrictions regarding WikiLeaks. For some U.S. intelligence officials, this was a welcome change. “There was immense hostility to WikiLeaks in the beginning from the intelligence community,” said Litt.

Vault 7 prompted “a brand-new mindset with the administration for rethinking how to look at WikiLeaks as an adversarial actor,” Evanina said. “That was new, and it was refreshing for the intelligence community and the law enforcement community.” Updates on Assange were frequently included in Trump’s President’s Daily Brief, a top-secret document prepared by U.S. intelligence agencies that summarizes the day’s most critical national security issues, according to a former national security official.

The immediate question facing Pompeo and the CIA was how to hit back against WikiLeaks and Assange. Agency officials found the answer in a legal sleight of hand. Usually, for U.S. intelligence to secretly interfere with the activities of any foreign actor, the president must sign a document called a “finding” that authorizes such covert action, which must also be briefed to the House and Senate intelligence committees. In very sensitive cases, notification is limited to Congress’s so-called Gang of Eight — the four leaders of the House and Senate, plus the chairperson and ranking member of the two committees.

But there is an important carveout. Many of the same actions, if taken against another spy service, are considered “offensive counterintelligence” activities, which the CIA is allowed to conduct without getting a presidential finding or having to brief Congress, according to several former intelligence officials.

Often, the CIA makes these decisions internally, based on interpretations of so-called “common law” passed down in secret within the agency’s legal corps. “I don’t think people realize how much [the] CIA can do under offensive [counterintelligence] and how there is minimal oversight of it,” said a former official.

The difficulty in proving that WikiLeaks was operating at the direct behest of the Kremlin was a major factor behind the CIA’s move to designate the group as a hostile intelligence service, according to a former senior counterintelligence official. “There was a lot of legal debate on: Are they operating as a Russian agent?” said the former official. “It wasn’t clear they were, so the question was, can it be reframed on them being a hostile entity.”

Intelligence community lawyers decided that it could. When Pompeo declared WikiLeaks “a non-state hostile intelligence service,” he was neither speaking off the cuff nor repeating a phrase concocted by a CIA speechwriter. “That phrase was chosen advisedly and reflected the view of the administration,” a former Trump administration official said.

But Pompeo’s declaration surprised Litt, who had left his position as general counsel of the Office of the Director for National Intelligence less than three months previously. “Based on the information that I had seen, I thought he was out over his skis on that,” Litt said.

For many senior intelligence officials, however, Pompeo’s designation of WikiLeaks was a positive step. “We all agreed that WikiLeaks was a hostile intelligence organization and should be dealt with accordingly,” said a former senior CIA official.

Soon after the speech, Pompeo asked a small group of senior CIA officers to figure out “the art of the possible” when it came to WikiLeaks, said another former senior CIA official. “He said, ‘Nothing’s off limits, don’t self-censor yourself. I need operational ideas from you. I’ll worry about the lawyers in Washington.’” CIA headquarters in Langley, Va., sent messages directing CIA stations and bases worldwide to prioritize collection on WikiLeaks, according to the former senior agency official.

The CIA’s designation of WikiLeaks as a non-state hostile intelligence service enabled “the doubling down of efforts globally and domestically on collection” against the group, Evanina said. Those efforts included tracking the movements and communications of Assange and other top WikiLeaks figures by “tasking more on the tech side, recruiting more on the human side,” said another former senior counterintelligence official.

This was no easy task. WikiLeaks associates were “super-paranoid people,” and the CIA estimated that only a handful of individuals had access to the Vault 7 materials the agency wanted to retrieve, said a former intelligence official. Those individuals employed security measures that made obtaining the information difficult, including keeping it on encrypted drives that they either carried on their persons or locked in safes, according to former officials.

WikiLeaks claimed it had published only a fraction of the Vault 7 documents in its possession. So, what if U.S. intelligence found a tranche of those unpublished materials online? At the White House, officials began planning for that scenario. Could the United States launch a cyberattack on a server being used by WikiLeaks to house these documents?

Officials weren’t sure if the Defense Department had the authority to do so at the time, absent the president’s signature. Alternatively, they suggested, perhaps the CIA could carry out the same action under the agency’s offensive counterintelligence powers. After all, officials reasoned, the CIA would be erasing its own documents. However, U.S. spies never located a copy of the unpublished Vault 7 materials online, so the discussion was ultimately moot, according to a former national security official.

Nonetheless, the CIA had some successes. By mid-2017, U.S. spies had excellent intelligence on numerous WikiLeaks members and associates, not just on Assange, said former officials. This included what these individuals were saying and who they were saying it to, where they were traveling or going to be at a given date and time, and what platforms these individuals were communicating on, according to former officials.

U.S. spy agencies developed good intelligence on WikiLeaks associates’ “patterns of life,” particularly their travels within Europe, said a former national security official. U.S. intelligence was particularly keen on information documenting travel by WikiLeaks associates to Russia or countries in Russia’s orbit, according to the former official.

At the CIA, the new designation meant Assange and WikiLeaks would go from “a target of collection to a target of disruption,” said a former senior CIA official. Proposals began percolating upward within the CIA and the NSC to undertake various disruptive activities — the core of “offensive counterintelligence” — against WikiLeaks. These included paralyzing its digital infrastructure, disrupting its communications, provoking internal disputes within the organization by planting damaging information, and stealing WikiLeaks members’ electronic devices, according to three former officials.

Infiltrating the group, either with a real person or by inventing a cyber persona to gain the group’s confidence, was quickly dismissed as unlikely to succeed because the senior WikiLeaks figures were so security-conscious, according to former intelligence officials. Sowing discord within the group seemed an easier route to success, in part because “those guys hated each other and fought all the time,” a former intelligence official said.

But many of the other ideas were “not ready for prime time,” said the former intelligence official.

“Some dude affiliated with WikiLeaks was moving around the world, and they wanted to go steal his computer because they thought he might have” Vault 7 files, said the former official.

The official was unable to identify that individual. But some of these proposals may have been eventually approved. In December 2020, a German hacker closely affiliated with WikiLeaks who assisted with the Vault 7 publications claimed that there had been an attempt to break into his apartment, which he had secured with an elaborate locking system. The hacker, Andy Müller-Maguhn, also said he had been tailed by mysterious figures and that his encrypted telephone had been bugged.

Asked whether the CIA had broken into WikiLeaks’ associates’ homes and stolen or wiped their hard drives, a former intelligence official declined to go into detail but said that “some actions were taken.”

By the summer of 2017, the CIA’s proposals were setting off alarm bells at the National Security Council. “WikiLeaks was a complete obsession of Pompeo’s,” said a former Trump administration national security official. “After Vault 7, Pompeo and [Deputy CIA Director Gina] Haspel wanted vengeance on Assange.”

At meetings between senior Trump administration officials after WikiLeaks started publishing the Vault 7 materials, Pompeo began discussing kidnapping Assange, according to four former officials. While the notion of kidnapping Assange preceded Pompeo’s arrival at Langley, the new director championed the proposals, according to former officials.

Pompeo and others at the agency proposed abducting Assange from the embassy and surreptitiously bringing him back to the United States via a third country — a process known as rendition. The idea was to “break into the embassy, drag [Assange] out and bring him to where we want,” said a former intelligence official. A less extreme version of the proposal involved U.S. operatives snatching Assange from the embassy and turning him over to British authorities.

Such actions were sure to create a diplomatic and political firestorm, as they would have involved violating the sanctity of the Ecuadorian Embassy before kidnapping the citizen of a critical U.S. partner — Australia — in the capital of the United Kingdom, the United States’ closest ally. Trying to seize Assange from an embassy in the British capital struck some as “ridiculous,” said the former intelligence official. “This isn’t Pakistan or Egypt — we’re talking about London.”

British acquiescence was far from assured. Former officials differ on how much the U.K. government knew about the CIA’s rendition plans for Assange, but at some point, American officials did raise the issue with their British counterparts.

“There was a discussion with the Brits about turning the other cheek or looking the other way when a team of guys went inside and did a rendition,” said a former senior counterintelligence official. “But the British said, ‘No way, you’re not doing that on our territory, that ain’t happening.’” The British Embassy in Washington did not return a request for comment.

In addition to diplomatic concerns about rendition, some NSC officials believed that abducting Assange would be clearly illegal. “You can’t throw people in a car and kidnap them,” said a former national security official.

In fact, said this former official, for some NSC personnel, “This was the key question: Was it possible to render Assange under [the CIA’s] offensive counterintelligence” authorities? In this former official’s thinking, those powers were meant to enable traditional spy-versus-spy activities, “not the same kind of crap we pulled in the war on terror.”

Some discussions even went beyond kidnapping. U.S. officials had also considered killing Assange, according to three former officials. One of those officials said he was briefed on a spring 2017 meeting in which the president asked whether the CIA could assassinate Assange and provide him “options” for how to do so.

“It was viewed as unhinged and ridiculous,” recalled this former senior CIA official of the suggestion.

It’s unclear how serious the proposals to kill Assange really were. “I was told they were just spitballing,” said a former senior counterintelligence official briefed on the discussions about “kinetic options” regarding the WikiLeaks founder. “It was just Trump being Trump."

Nonetheless, at roughly the same time, agency executives requested and received “sketches” of plans for killing Assange and other Europe-based WikiLeaks members who had access to Vault 7 materials, said a former intelligence official. There were discussions “on whether killing Assange was possible and whether it was legal,” the former official said.

Yahoo News could not confirm if these proposals made it to the White House. Some officials with knowledge of the rendition proposals said they had heard no discussions about assassinating Assange.

In a statement to Yahoo News, Trump denied that he ever considered having Assange assassinated. “It’s totally false, it never happened,” he said. Trump seemed to express some sympathy for Assange’s plight. “In fact, I think he’s been treated very badly,” he added.

Whatever Trump’s view of the matter at the time, his NSC lawyers were bulwarks against the CIA’s potentially illegal proposals, according to former officials. “While people think the Trump administration didn’t believe in the rule of law, they had good lawyers who were paying attention to it,” said a former senior intelligence official.

The rendition talk deeply alarmed some senior administration officials. John Eisenberg, the top NSC lawyer, and Michael Ellis, his deputy, worried that “Pompeo is advocating things that are not likely to be legal,” including “rendition-type activity,” said a former national security official. Eisenberg wrote to CIA General Counsel Courtney Simmons Elwood expressing his concerns about the agency’s WikiLeaks-related proposals, according to another Trump national security official.

It’s unclear how much Elwood knew about the proposals. “When Pompeo took over, he cut the lawyers out of a lot of things,” said a former senior intelligence community attorney.

Pompeo’s ready access to the Oval Office, where he would meet with Trump alone, exacerbated the lawyers’ fears. Eisenberg fretted that the CIA director was leaving those meetings with authorities or approvals signed by the president that Eisenberg knew nothing about, according to former officials.

NSC officials also worried about the timing of the potential Assange kidnapping. Discussions about rendering Assange occurred before the Justice Department filed any criminal charges against him, even under seal — meaning that the CIA could have kidnapped Assange from the embassy without any legal basis to try him in the United States.

Eisenberg urged Justice Department officials to accelerate their drafting of charges against Assange, in case the CIA’s rendition plans moved forward, according to former officials. The White House told Attorney General Jeff Sessions that if prosecutors had grounds to indict Assange they should hurry up and do so, according to a former senior administration official.

Things got more complicated in May 2017, when the Swedes dropped their rape investigation into Assange, who had always denied the allegations. White House officials developed a backup plan: The British would hold Assange on a bail jumping charge, giving Justice Department prosecutors a 48-hour delay to rush through an indictment.

Eisenberg was concerned about the legal implications of rendering Assange without criminal charges in place, according to a former national security official. Absent an indictment, where would the agency bring him, said another former official who attended NSC meetings on the topic. “Were we going to go back to ‘black sites’?”

As U.S. officials debated the legality of kidnapping Assange, they came to believe that they were racing against the clock. Intelligence reports warned that Russia had its own plans to sneak the WikiLeaks leader out of the embassy and fly him to Moscow, according to Evanina, the top U.S. counterintelligence official from 2014 through early 2021.

The United States “had exquisite collection of his plans and intentions,” said Evanina. “We were very confident that we were able to mitigate any of those [escape] attempts.”

Officials became particularly concerned when suspected Russian operatives in diplomatic vehicles near the Ecuadorian Embassy were observed practicing a “starburst” maneuver, a common tactic for spy services, whereby multiple operatives suddenly scatter to escape surveillance, according to former officials. This may have been a practice run for an exfiltration, potentially coordinated with the Ecuadorians, to get Assange out of the embassy and whisk him out of the country, U.S. officials believed.

“The Ecuadorians would tip off the Russians that they were going to be releasing Assange on the street, and then the Russians would pick him up and spirit him back to Russia,” said a former national security official.

Officials developed multiple tactical plans to thwart any Kremlin attempt to spring Assange, some of which envisioned clashes with Russian operatives in the British capital. “There could be anything from a fistfight to a gunfight to cars running into each other,” said a former senior Trump administration official.

U.S. officials disagreed over how to interdict Assange if he attempted to escape. A proposal to initiate a car crash to halt Assange’s vehicle was not only a “borderline” or “extralegal” course of action — “something we’d do in Afghanistan, but not in the U.K.” — but was also particularly sensitive since Assange was likely going to be transported in a Russian diplomatic vehicle, said a former national security official.

If the Russians managed to get Assange onto a plane, U.S. or British operatives would prevent it from taking off by blocking it with a car on the runway, hovering a helicopter over it or shooting out its tires, according to a former senior Trump administration official. In the unlikely event that the Russians succeeded in getting airborne, officials planned to ask European countries to deny the plane overflight rights, the former official said.

Eventually, the United States and the U.K. developed a “joint plan” to prevent Assange from absconding and giving Vladimir Putin the sort of propaganda coup he had enjoyed when Snowden fled to Russia in 2013, Evanina said.

Russia's President Vladimir Putin speaks during his press conference at the Kremlin in Moscow, on July 1, 2013. Putin said today that his country had never extradited anyone before and added that US leaker Edward Snowden could remain in Moscow if he stopped issuing his leaks. (Alexander Nemenov/AFP via Getty Images)

“It’s not just him getting to Moscow and taking secrets,” he said. “The second wind that Putin would get — he gets Snowden and now he gets Assange — it becomes a geopolitical win for him and his intelligence services.”

Evanina declined to comment on the plans to prevent Assange from escaping to Russia, but he suggested that the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance between the United States, the U.K., Canada, Australia and New Zealand was critical. “We were very confident within the Five Eyes that we would be able to prevent him from going there,” he said.

But testimony in a Spanish criminal investigation strongly suggests that U.S. intelligence may also have had inside help keeping tabs on Assange’s plans.

By late 2015, Ecuador had hired a Spanish security company called UC Global to protect the country’s London embassy, where Assange had already spent several years running WikiLeaks from his living quarters. Unbeknownst to Ecuador, however, by mid-2017 UC Global was also working for U.S. intelligence, according to two former employees who testified in a Spanish criminal investigation first reported by the newspaper El País.

The Spanish firm was providing U.S. intelligence agencies with detailed reports of Assange’s activities and visitors as well as video and audio surveillance of Assange from secretly installed devices in the embassy, the employees testified. A former U.S. national security official confirmed that U.S. intelligence had access to video and audio feeds of Assange within the embassy but declined to specify how it acquired them.

By December 2017, the plan to get Assange to Russia appeared to be ready. UC Global had learned that Assange would “receive a diplomatic passport from Ecuadorian authorities, with the aim of leaving the embassy to transit to a third state,” a former employee said. On Dec. 15, Ecuador made Assange an official diplomat of that country and planned to assign him to its embassy in Moscow, according to documents obtained by the Associated Press.

Assange said he “was not aware” of the plan struck by the Ecuadorian foreign minister to assign him to Moscow, and refused to “accept that assignment,” said Fidel Narvaez, who was the first secretary at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London in 2017 and 2018.

Narvaez told Yahoo News that he was directed by his superiors to try and get Assange accredited as a diplomat to the London embassy. “However, Ecuador did have a plan B,” said Narvaez, “and I understood it was to be Russia.”

Aitor Martínez, a Spanish lawyer for Assange who worked closely with Ecuador on getting Assange his diplomat status, also said the Ecuadorian foreign minister presented the Russia assignment to Assange as a fait accompli — and that Assange, when he heard about it, immediately rejected the idea.

On Dec. 21, the Justice Department secretly charged Assange, increasing the chances of legal extradition to the United States. That same day, UC Global recorded a meeting held between Assange and the head of Ecuador’s intelligence service to discuss Assange’s escape plan, according to El País. “Hours after the meeting” the U.S. ambassador relayed his knowledge of the plan to his Ecuadorian counterparts, reported El País.