BAGHDAD, — When Iraq's Deputy Prime Minister Hussain al-Shahristani met Exxon Mobil executives in Baghdad two months ago, he could hardly control his emotions. His anger boiling over, the Iraqi oil chief threatened to kick the Americans out of the country.

With Exxon and other foreign oil majors upsetting Baghdad by signing exploration deals with autonomous Kurdistan region, Shahristani's rage was not hard to understand.

But barking threats at Exxon may be all Baghdad can do.

Foreign oil firms and autonomous Kurdistan have tested Shahristani's patience for months by drawing up oil accords the central government dismisses as illegal. Baghdad insists it alone has the right to export Iraqi crude.

Nine months after U.S. troops left, the oil contracts dispute is part of a broader political feud between the Baghdad government and Kurdistan over oil rights, territory and regional autonomy that is straining Iraq's uneasy federal union.

Other majors Chevron, Total and Gazprom have joined Exxon with their own deals in Kurdistan, provoking warnings from Baghdad their southern Iraqi oil deals with the federal government might be at risk.

But the might of Exxon has caught the oil ministry in a bind and officials say privately any action against the firm is unlikely in the near future. With few assets exposed to Baghdad, other majors in Kurdistan may also escape unpunished.

Exxon operates West Qurna-1, the 8.7 billion-barrel field in southern Iraq, producing 406,000 barrels per day, and earning a healthy chunk of Iraq's central government petrodollars.

"We have to think twice about pushing Exxon out of West Qurna. It's the operator of a field with crucial output. It's a problem, a big problem for us," said a senior oil official who was involved in drafting the West Qurna contract.

FRUSTRATED BAGHDAD

Executives from Exxon Mobil would have known even before the July meeting with Shahristani that they had angered the Baghdad government, but analysts say it was a deliberate calculation as they played rival interests in Iraq off against each other.

Exxon was the first company to flex its muscle and challenge Baghdad's authority by independently signing for six blocs to explore for oil with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in October last year.

Eager to rebuild its dilapidated infrastructure, Iraq has signed a series of contracts with foreign companies that target total oil production capacity of 12 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2017, up from about 3 million bpd.

Most analysts now see 6 million to 7 million bpd as more realistic.

The Exxon dilemma has left Shahristani in a difficult position. Iraqi frustration was clear in Shahristani's dealings with Exxon, according to sources aware of the recent talks.

"It was a really tense meeting. Shahristani was tough with Exxon's officials and warned them angrily they could lose the West Qurna contract if they started work in Kurdistan," an industry source told Reuters.

"The atmosphere heated up when Exxon said they would consider legal action."

COMPLEX POLITICS

Yet the complex politics of Iraq may also shield Exxon.

The oil row is just the latest complication in a long-running and deep-ranging dispute between Iraq's Shi'ite Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki in Baghdad and Kurdistan's President Masoud Barzani based in its capital, Arbil.

Maliki has gone as far as asking U.S. President Barack Obama to force Exxon to pull out of the deal, claiming the firm's actions are a threat to peace.

"The oil ministry isn't the party to decide what to do with Exxon now because it's become a political issue," another oil ministry official told Reuters.

Analysts and officials say Exxon has been clever, playing Baghdad and Arbil off each other with aplomb.

The tactic: securing lucrative deals in Kurdistan while sending signals to Baghdad that it may freeze its huge operations in the south.

"It's obvious to us that Exxon put the Kurdistan deals in its pocket, then sat back and crossed its arms waiting to see what Arbil and Baghdad would do," said an oil ministry official.

Some analysts say the firm is deliberately exploiting the political situation.

"Exxon chose the perfect moment to jump into Kurdistan and take advantage of the disputes over everything between Arbil and Baghdad," Baghdad-based oil analyst, Hamza al-Jawahiri, said.

The OPEC member has no binding hydrocarbon law more than nine years after the toppling of Saddam Hussein. Final passage of a 2007 draft has been delayed by political infighting, which has also played into the hands of Exxon and the other firms.

"The lack of an oil law has helped to open a narrow path for oil companies into Kurdistan. They had the foresight to realize that any eventual agreement will make them a winner at the end of the day," said Ali Shallal, an Iraqi legal expert who specializes in drafting oil contracts.

Kurdistan has enjoyed more stability and security than the rest of Iraq, and its potential resources have already drawn smaller oil players such as Norway's DNO and Gulf Keystone. But its bickering with Baghdad had kept majors away until now.

That some companies are unhappy with Baghdad's contract terms has not been lost on Arbil. Foreign firms already consider the production-sharing deals in Kurdistan a far better arrangement than Baghdad's fee-for-service contracts. Some are already seeking to renegotiate.

"They will most likely have a stronger hand than they did when the auctions were first launched," said Samuel Ciszuk, an oil consultant at UK-based KBC Energy Economics.

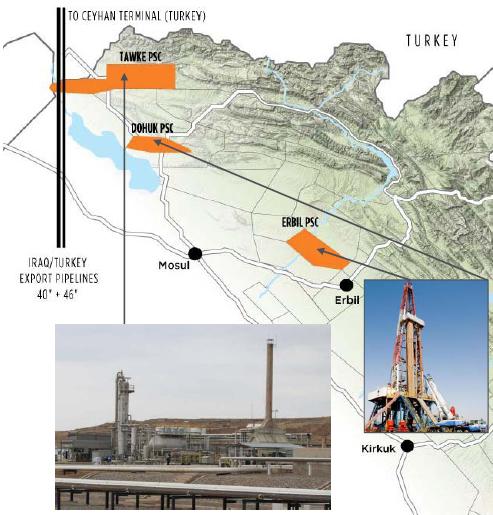

Whether Kurdistan will use the deals to try to push for more independence remains to be seen. But it is already looking to have its own export pipeline to the Turkish port of Ceyhan by 2014, aiming to reduce its energy reliance on Baghdad.

The knotty regional politics involving Iraq, Kurdistan, Turkey - further complicated by the conflict in neighboring Syria - means that is not yet a sure thing.

For now, though, there are no signs of foreign companies backing away from their new relationships with the Kurds.

"Exxon and the other firms have realized the only way to offset the modest profits generated from Baghdad deals is to invest in Kurdistan for extra profits and less risks," Ali Shallal said.